Learning Swedish Vocabulary

Although most of you would agree that any language is made up with – well, words, I encounter endless numbers of students that have a difficult time integrating vocabulary learning in their Swedish studies. Although some of them have made a conscious efforts not to learn words (planning to save that project for later), most of them struggle because of poor technique. As I mostly work with intermediate and advanced Swedish, vocabulary acquisition, integration and implementation are inevitable and necessary measures for progress.

Be consistent

Five or ten minutes of revision on a daily basis is much more effective and efficient than three hours the night before your class. It takes three weeks to get into a good habit, it is worth the effort.

Make an effort

A common mistake is to revise vocabulary through reading, or merely looking. This is not a particularly effective technique, unless you have an extraordinary photographic memory. Just like lifting weights (rather than looking at them) will help you build muscles, making an effort when learning new words will make them stick.

- Reading out aloud will involve many more parts of your brain than reading silently. This way, you can also rely on muscle memory.

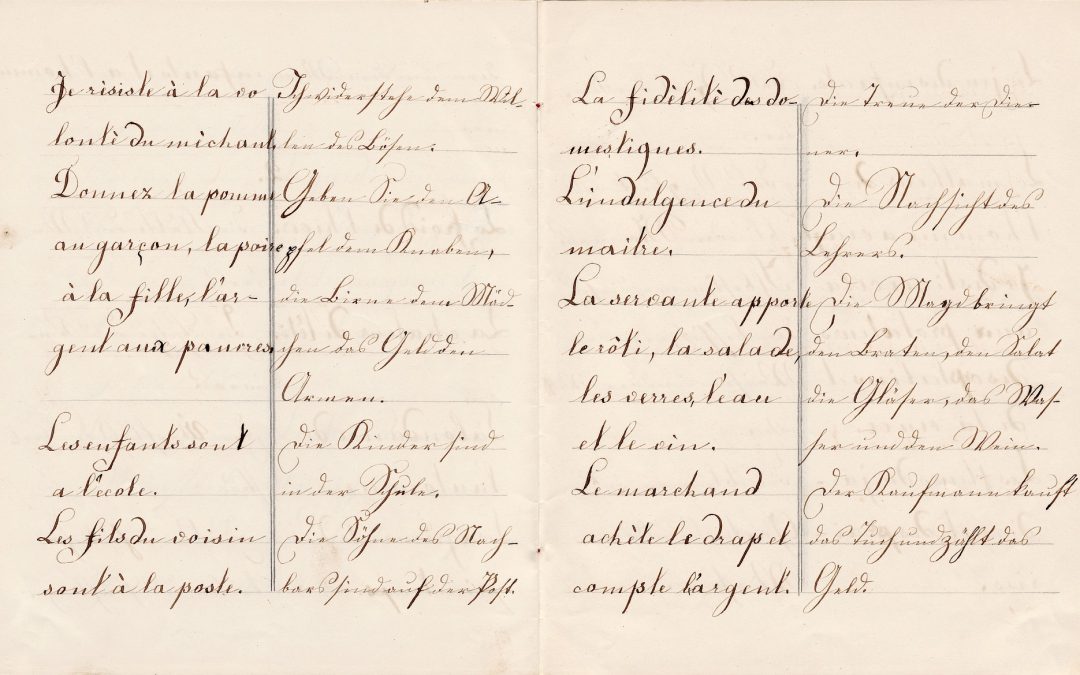

- Writing and re-writing words and phrases serves the same purpose, with more focus on orthography than pronunciation, of course..

- Testing yourself is not only a great idea to see how much you already know, but also to make your brain make that extra effort of – exactly, relying on memory. Flash-cards, folding pages in your notebooks, asking a friend to test you.

Contextualise

Actually, remembering words of their context makes it much more difficult. You know the textbook you use for your studies. Read the dialogues or the texts aloud, copy important phrases in writing. When you put a word in a context, it will become much more meaningful and you are more likely to remember it. You probably agree that it would be much easier to memorise a song than a full page from a phonebook (when these still existed).

Relate

When reading a text, write down similar phrases that relate to your own life. If you are learning, say, personal attributes, write a short text describing a person you know well rather than an imaginary, abstract figure. If you are learning the clock and times of the day, make a schedule where you specify what you normally do at these hours.

What about the gender of nouns?

This, apparently, is what most prospective of students fear. En or ett? Many of them tell me of how they fail at this before they even start.

There is a curious mistake here, that a majority of my students make. They memorise the noun by itself, and then somehow ‘tag’ it, as belonging to one of the two categories.

A few years ago, I started asking my students why so many of stick to this technique, although it does not work. To my surprise, they all gave me the same answer. They believe they ‘save memory’ by doing this, that is, that the unit hus somehow ‘takes less space in their brains’ than ett hus or huset. Whereas this may be a good method for efficiency for digital devices, our brains seem to work the opposite. In fact, it is much easier to memorise and remember a phrase such as huset, or even better, huset är gammalt och stort rather than hus – #ett, despite it being longer and more complex. This again, relates back to what I said about creating contexts rather than approaching vocabulary through abstract systems. Another advantage with learning phrases like this, rather than the smallest possible units, is that you will reinforce your knowledge of grammar.

And what about the verbs?

In your dictionary, paper or digital, verbs are traditionally presented in the infinitive form. In many languages, such as French, this is very useful, because you know from the infinitive how to conjugate them. In some languages, such as English, it does not even matter.

In Swedish, however, the infinitive is a little deceptive. Consider this:

att stänga [to close]

att öppna [to open]

att dansa [to dance]

att läsa [to read, or to study]

From the information given in the infinitive form (all here ending with an a) you have no clues how to conjugate these verbs:

But just looking at the imperative (stäng!, öppna!, dansa!, läs!), or the present tense (stänger, öppnar, dansar, läser), more clues are immediately available, as you will know whether you are dealing with an -ar verb (group 1) or an -er verb (groups 2a and 2b). Therefore, I strongly recommend you to revise and memorise verbs in the imperative or the present tense, and derive other tenses (and the infinitive) from there.